My grandmother was born in 1926. She was the second child of her parents’ marriage. My great-grandfather worked on the land on the Wash marshes, and my granny moved A Lot. They generally lived in the middle of nowhere.

This didn’t stop the entire family getting diphtheria in 1939. My great-grandmother had just lost her seventh child shortly after birth. My grandmother, aged thirteen, her older sister (14), and her younger sister (11) all went down with the disease at once.

Diphtheria is hideous. It starts with a nasty sore throat, not dissimilar to tonsillitis. The throat glands swell, the patient feels sick, there’s a very high temperature again similar to tonsillitis. However, unlike tonsillitis, the infection causes a membrane to form across the throat, effectively suffocating the patient. And it is spread by droplet infection, meaning it’s highly contagious among children, who are crap at covering their mouth when they cough.

There was no effective treatment for diphtheria in 1939. There was no penicillin. However, doctors were legally obliged to inform the authorities and contain the source of infection. So, my granny and her two sisters were sent to the isolation hospital in Wisbech (now Manor Gardens, off Barton Road). The hospital was deliberately sited away from the town.

This was not a short stay. They were in there for six weeks. For the first couple of weeks, they had to lie flat at all times, and were gradually allowed to sit up more as the dangerous period passed. My great-grandparents were not allowed physical contact. They lived on Terrington St Clement marsh at the time, over eleven miles from the hospital. They could not drive. Visiting was done through a glass wall on the ward. Meanwhile, the three sisters watched other children come in. They watched children have makeshift tracheotomies to try and keep their airway open. They watched other children die.

Meanwhile, my granny’s younger two siblings (aged 8 and 3) went down with a milder form of diphtheria. My great-grandmother, recently bereaved, chose not to consult a doctor because she couldn’t bear for them to go to the isolation hospital as well.

My grandmother and all her siblings survived, without need for surgery. They were fortunate. All their sheets, toys, clothing and personal items were burned when they left the hospital, rather than risk re-infection. It took weeks to de-institutionalise themselves when they got home, so rigorous was the hospital regime.

My grandmother died in 2001, aged 75. She never forgot her time in the isolation hospital. We once went to see if we could find it in Wisbech – it had been demolished ready to build Manor Gardens at the time, but the gates were still there. It’s all gone now. She carried that memory for sixty two years, long after her parents had died. Her eldest sister, who suffered with her, is still alive. This is living memory.

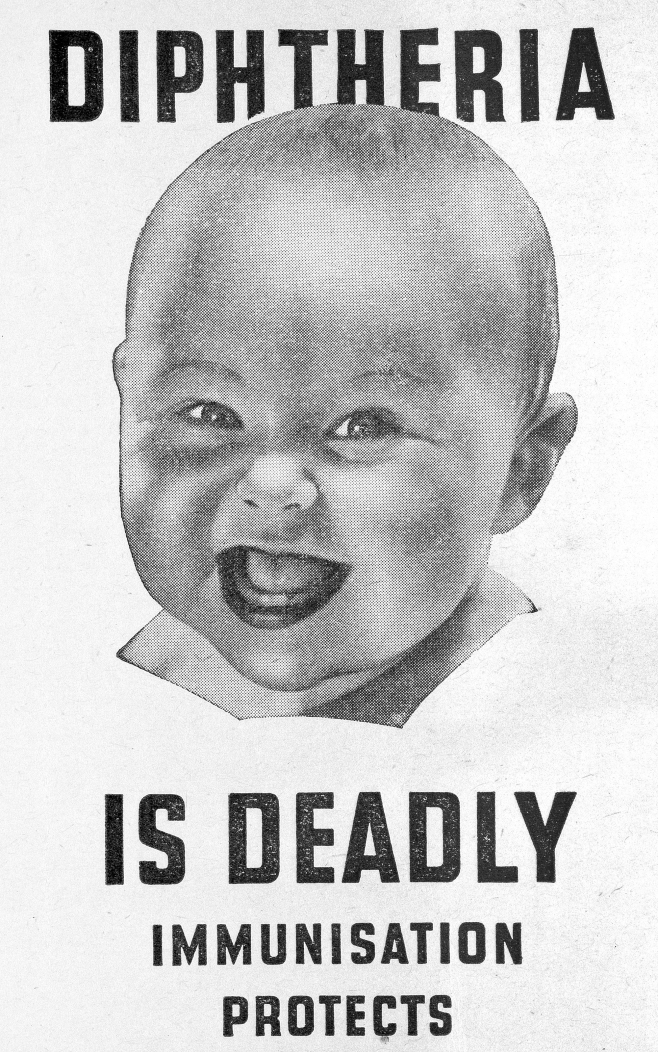

Diphtheria has been part of routine infant vaccination in Britain since approximately 1962, along with poliomyelitis (which killed and disabled thousands in the early 1950s), pertussis (whooping cough) and tetanus (endemic in the soil, causes respiratory paralysis).

So, we have vaccination now. We have antibiotics that work. We don’t need isolation hospitals anymore. But the more parents that choose not to vaccinate their children against diseases that kill indiscriminately, the more likely it is that some form of fever hospital will be required.

Get in touch with your own family research problems and questions using the contact page above.