My last blog was about adultery and divorce. But divorce was only an avenue open to the very rich until divorce law was reformed in the 1920s, and again in the 1930s. What happened before then?

Bigamy. A crime where the punishment (a maximum of seven years in prison) was usually worth the risk, since it was so difficult to detect. But a bigamous marriage was not necessarily a happy one.

Henry Strutt was born in the City of London in 1847. He was the youngest child of Henry Warren Strutt, an admiralty clerk, and Henrietta Wilson. The Strutts lived in Grays Inn Lane, near Grays Inn, and demolished in the 1880s.

Henry may have been spoiled, as the youngest, with two older sisters fussing over him. He followed his father into a clerking job. In the spring of 1869, he impregnated Florence Mary Ann Foy. Florence was ten years older than Henry, the unmarried daughter of a merchant. It appears to have been love rather than arranged, and they married in October 1869. Six weeks later, Henry’s father died, leaving £1000 in his will. The modern equivalent is about half a million pounds: not a huge amount, but enough to settle down with.

Henry and Florence had five children across the next nine years, but the marriage was over by 1881. Henry does not appear on that census, and may have joined the army. Florence was living with her widowed mother-in-law, and four of their children. The eldest child, Florence Julia, had been sent to live in the Metropolitan and Police Officer’s Orphanage. It is unclear how this came to be organised, as Henry was not dead- perhaps he disappeared abruptly enough to convince all who knew him he was dead – and men had to have paid a penny a week as an insurance subscription to allow their children to attend if they died. Henry’s mother died in 1883, and by 1891, Florence claimed to be a widow on the census.

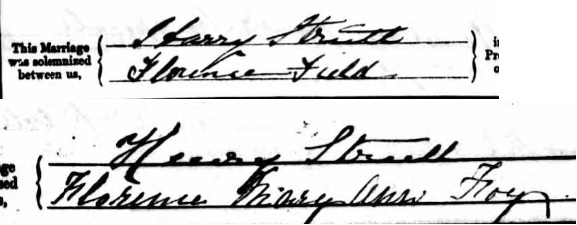

But Henry was not dead – he had reinvented himself in North London. Now calling himself Harry, and claiming to have been born in 1853, he had got himself a job at Pentonville prison as a warder. He had also met Florence Field, a girl from Dun Stew in Oxfordshire. Florence’s first child was born in Bournemouth in 1887, and was probably not Harry’s. Her second child, Harry Cecil, born in Islington in 1889, definitely was. By 1891, they were living together near the prison. In October 1892, with Florence pregnant again, they married bigamously in Barnsbury. Harry had changed his name and age, but he still used his real father’s name on the marriage registry, which is how I was able to trace him.

Harry and Florence quickly moved to Oxford after their marriage, presumably to avoid his bigamy being detected. Things did not go well. The baby Florence was expecting died shortly after birth. A final baby, Ethel, was born in February 1895. In January 1896, Florence’s daughter, eight-year-old Florence Louisa, stole a number of items from outside a shop. These items were passed to her mother, who tried to conceal them when the police came knocking. Florence Louisa was bound over to keep the peace, but Florence was sentenced to six weeks in prison for recieving stolen goods. This proved disastrous for the family, as Harry subsequently lost his job, and the family had so little money that Florence had to pawn her sewing machine, losing her only source of potential income. Both Harry and Florence placed advertisements in the newspaper following this incident begging for help, Harry referring to ten years served in the army.1

Harry and Florence were living apart in 1901, and Florence Louisa had been sent to live in a Nazareth orphanage, run by nuns. The couple reconciled, but separated again in the autumn of 1904. Harry lost his job at the University Stores in March 1905.

On 26th April 1905, Harry was found dead in his lodgings. He had swallowed potassium cyanide. His landlady was surprised to learn that he was married, but testified that he had frequently expressed suicidal thoughts. Harry left three notes. The first blamed the loss of his job squarely on his wife, and her ‘quarrelling and nagging’, and asked his landlady to send his belongings to his daughter Ethel. The second mentioned the address to send the belongings to. The third was addressed to Ethel, then aged ten years and two months:

God bless you my darling Ethel. My troubles are more than I can bear – Dad

Florence was present at the inquest, but not questioned, which is a curious omission. However, their son, Harry Cecil, then aged sixteen was questioned. He didn’t know why his parents were living apart as they had ‘such a happy home’. He also testified that he did not know where his father was living, although he had seen him in the city. This is an interesting point: Harry had no difficulty vanishing and keeping his movements secret, even while living within a mile of his family. Harry Cecil testified that his father owned potassium cyanide for cleaning his old military accoutrements. His death was registered as suicide while of unsound mind. His other family were not mentioned.

Florence never remarried. She died in Oxford in 1909, shortly before she turned forty-three.

Florence Mary Ann, his first wife, also never remarried, possibly because she suspected her husband was still alive. She died in 1929, aged ninety-one.

Harry had five children with his first wife, and three with his second. All of his first family were raised believing their father had died – all the adult children listed their father as a deceased clerk on their marriage certificates. They were: Florence Julia (1869-1939), William Warren (1870-1883), Alice Harry (1873-1931), Henry Russell (1875-1941) and Mabel Marion (1878-1931).

His three younger children were: Harry Cecil (1889-1915, killed in action), Millicent (born and died 1893) and Ethel. I am unable to trace Ethel, although she was still living in England in 1915. She may have emigrated.

It is highly unlikely Harry’s second lot of children knew about the first, and vice versa. The art of getting away with bigamy was total secrecy, and although it seems Henry Strutt managed this admirably, it came at a price beyond money.

- 1. Oxford Times, 18th January and 26th March 1896. I can find no record of Harry serving in the army, although this would explain where he was between the birth of his youngest child from his first marriage in 1878, and the birth of his son with Florence Field in 1888. It is possible that he enlisted using a false name, and was thus able to ‘disappear’.

One thought on “The Lies of Henry Strutt”

Comments are closed.