Since I last wrote, I’ve begun my PhD and it’s taking up a lot of time. As you’d expect. One does not merely walk through a PhD. However, I’m finishing up some commissions I took on before I even knew for definite I was DOING a PhD. And I have found a story that combines all my favourite things: death, inquests, community and justice.

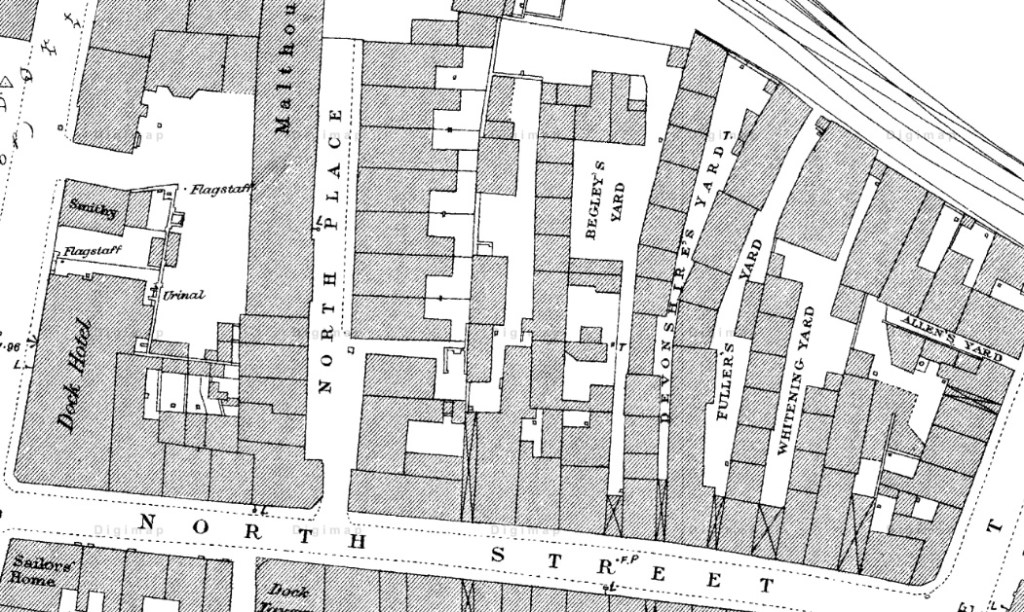

Our story begins in King’s Lynn in 1882. King’s Lynn was an important medieval port, but by the late ninteenth century, the main industry was fishing rather than shipping. Fishing families lived in tiny yards in North End, an area famed for being rough. One such yard was Whitening Yard, off North Street:

This is now a garage near the junction with John Kennedy Way. Several families lived here, in filthy conditions, but our story concerns the Newmans and the Baileys. Elias and Eliza Newman had married in 1874. Elias and Eliza had been living together for several years before their marriage, and had a brood of illegitimate and legitimate children – all perfectly normal for the area. Eliza had one son from her first marriage: James Stannard, known as Jim, born in March 1863, shortly after his father’s death. She had a further five children with Elias. Harriet, Agnes and Charles Newman were aged nine, five and three at the time of this particular incident. Elias sold fish for a living.

The Baileys were a fishing family. William and Mary Ann Bailey had married in 1860. Mary Ann was fourteen at the time, and over the next twenty-two years, gave birth to thirteen children. In 1882, only six were still alive. They were Elizabeth Maull, freshly married, aged twenty-two, with a daughter of her own, Harriet (18), Naomi (14), Susannah (11), Billy (8) and baby Harry (1). They had moved into Whitening Yard from nearby North Place relatively recently.

Whit Monday, the monday following Whitsun (the seventh Sunday after Easter) had been a traditional holiday for many moons before it was legally codified in 1871. Whit Monday fell on 29th May in 1882, and most people in the yards had the day off. Eliza Newman went to Hunstanton with her sister, and left her little children to have a tea party in the yard, overseen by a teenage neighbour. They set up a tea table and a little tent. Jim Stannard took his girlfriend, Kate Cannon, out for a romantic walk about Lynn.

The Baileys were also at home, but in foul temper. The Newman children’s tent was blocking access to their house. It’s difficult to precisely work out the order of the fracas that followed, but it seems that William Bailey was angry that his access was blocked, and threw their tent down, and kicked the tea table over. Then Elizabeth Maull threw a bucket of mucky water at the children. The children were very upset, and Jim came home to find his little sisters and brother in tears. And he kicked off.

The Bailey women shouted at him from their kitchen window, calling him white-livered. It seems Jim and the Newmans had insulted the Baileys (probably referring to them being rough), and Jim shouted “IF YOU WANT ANYTHING, COME OUT”, a Victorian version of ‘come and have a go if you think you’re hard enough’.

Alas, the Baileys WERE hard enough, and they DID come out. Elizabeth, holding her fourteen-month-old daughter came out first and hit him with baby’s shoe (probably a small wooden clog). Jim pushed her, and all the other Baileys came to her aid. William (now almost fifty years old), Mary Ann and their three older daughters beat Jim about the head for about five minutes, before a neighbour – Mary Panton of which more anon – broke the fight up, and took Jim into his house to clean him up.

A few hours later, Jim went out to meet his girlfriend and best friend. He told them what had happened, and how much his head hurt and how weird he felt. By Wednesday, he felt unable to go to work, although he did go out on the Saturday.

The following Wednesday was 7th June, and by this point, Jim was suffering. His mother described him as delirious and mad, pulling at his head. A surgeon was called on the Friday, and decided he was mad and prescribed him ‘medicine’. God only knows what was in the medicine. Oddly, Mrs Newman did not tell the doctor about the fight.

On Sunday, the 11th June, almost a fornight after the fight, Mrs Newman obtained a medical order from the Board of Guardians, enabling another surgeon to visit Jim. This surgeon, Mr Barrett, attended Jim until his death. He thought Jim had typhus. It wasn’t until the 13th that Jim’s aunt (who is not named in the inquest or court papers, but was probably Charlotte Felgate, married to Eliza’s brother, and also resident in Whitening Yard) mentioned to the doctor that Jim had been in a fight two weeks earlier. The doctor diagnosed meningitis, but it was too late, Jim died that evening.

An inquest was called, and it was attended by half of North End. And a curious mixture of lies, self-defence and posturing followed. It was the usual practice for coroners to allow people accused of murder or manslaughter to speak under oath, with legal representation, to get an idea of what had happened. However, the Baileys were not invited to speak. Instead, a hodge podge of residents from Whitening Yard gave evidence as to what had happened on Whit Monday. Eliza’s evidence was useless – she hadn’t been home. Elias wasn’t called to give evidence, nor were the children whose tea party had been demolished. Robert Felgate, Eliza’s nephew (14) gave some evidence that there had been a fight. Sarah Anderson, who had been in charge of the Newman children (also aged 14) gave evidence, but also claimed that the fight had last for half an hour! Then Mary Ann Panton, who had ‘rescued’ Jim from the fight claimed not only that he had started it, but that he had been drunk, raving, and stripped to the waist. However, the Pantons were related to the Baileys, and the coroner dismissed her contradictory evidence out of hand. There were six families in the yard, including Elizabeth Maull’s in-laws. The sole unrelated witness was Charlotte Money, who testified that she had seen very little, but heard the fight and did not think Jim had sworn at the Baileys. She later married into the Benefer family, who were related to virtually everyone in Lynn’s fishing community. Finally, Jim’s best friend and girlfriend testified that he did not drink, was very quiet and had not been right since Whit Monday.

The inquest was adjourned to the Town Hall, since it was obviously a case of major local interest, and the medical evidence was heard. The postmortem showed that Jim had meningitis, although they could find no bruise or fracture from the fight. Neither of the doctors who attended Jim were willing to admit that they had misdiagnosed a traumatic brain injury, nor that they could have saved his life if they’d realised it earlier, but it wasn’t really their fault. After all, Jim was quite delirious by the time they were called in, and his mother hadn’t told them anything.

You see, it seems that Elias Newman did not want his family upsetting the neighbours. He did not want the family dragged through the press. Perhaps he bought fish from the Baileys, or was worried that the fishing community would stop selling him fish. He told Mary Ann Bailey that Jim had been out late on the Saturday night and come back drunk, and Mary reported this to the coroner. But all the evidence suggests this was a fabrication to plant the idea that Jim’s head injury was caused by a fight with an Unknown Stranger rather than their next-door neighbours. It is likely that he told his wife to keep the origin of Jim’s illness from the doctors – after all, it was her sister-in-law that told the doctor about the fight, not his mother. Elias did nothing to suppress the stories about his stepson being a drunkard, even though his best friend and girlfriend testified that he didn’t drink much.

However, when the coroner questioned Elias, he found him unreliable. Elias claimed that his stepson had come home drunk after Elias was in bed and then Elias had ‘seen him go up the stairs’. But how, if he was in bed upstairs? Caught in this lie, Elias left the stand.

Harriet Bailey then claimed that Jim had in fact hit the BABY, that SHE was holding which was not backed up by any other evidence. Every other witness claimed it was Elizabeth who went out first. The coroner’s jury found William Bailey, Mary Ann Bailey, Elizabeth Maull, Harriet Bailey and Naomi Bailey had killed Jim by manslaughter. They removed Naomi’s name from the indictment as she was only fourteen, but the other Baileys were sent to trial at Norwich Assize.

Their trial was held in August 1882. The evidence was the same as at the coroner’s court, with a few additional questions thrown in by the defence lawyer. The defence lawyer decided that the Baileys’ best way out was to claim that Jim was a drunk, and by battering a woman with a baby, got what was coming to him from a bunch of women. However, the jury were unconvinced by this – perhaps seeing the four Baileys, all strong from years of fishing and manual labour, they determined that Jim never stood a chance – and found them guilty.

William went to prison for a year. Mary Ann, Elizabeth and Harriet went to prison for eight months. Harriet was seven months pregnant at the time, and gave birth to her son in Norwich prison (in the castle) in October. The baby’s father had left Lynn by the time she came out of prison, and she married into the Benefer family. Elizabeth was also pregnant, and gave birth in prison at the end of 1882. The Baileys all returned to Lynn after serving their sentences, although William died in 1890. Mary then moved to Grimsby with family.

The Newmans also remained in Lynn, but both Elias and Eliza died in 1883, and their younger children were raised by relatives.

True’s Yard Museum at Lynn holds lots of information on these families, including photos of the Baileys.

This is the sort of case I hope to dig into when I get into the research element of my PhD. Was the coroner’s court a place where you could expect justice? A place for airing dirty laundry or a place where family secrets could be kept?

My ‘book’ is still closed for full commissions, but do get in touch with any other queries.

SOURCES: Lynn Advertiser, 24th June and 12th August 1882.

One thought on “The Delayed Death of Jim Stannard”

Comments are closed.