TW: Domestic violence, rape, suicide

My cousin, Linden Secker, is the head of biographical research at Holbeach Cemetery in Lincolnshire, and digs up stories about the people whose graves he looks after. Just before Christmas, he wrote about the sad suicide of Arthur Marriott, a divorced man who took prussic acid in a veterinary surgery in Holbeach. I am like a bloodhound when it comes to suspicious deaths that hint at marital woe, so I did some additional digging, and between us, the full story emerged. A story of perversion, abuse, terror and shame.

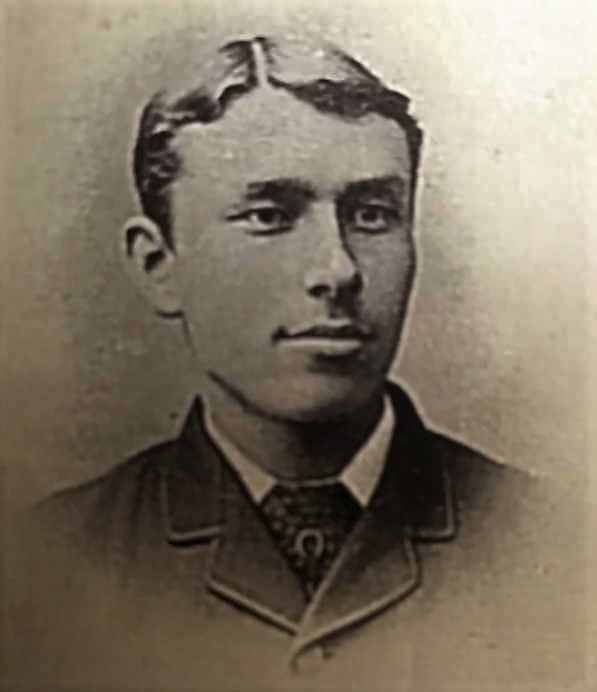

Arthur Marriott was born in Milton Malsor, a village a little south of Northampton, in the summer of 1866. He was the youngest child of Thomas and Mary Ann Marriott. His father was a Baptist minister, and Mary Ann was his second wife: they married in 1850, when Thomas was sixty-one, and Mary Ann was twenty-one. Despite the age gap, the marriage produced nine children, and Thomas was seventy-seven when his youngest child was born.

Perhaps inevitably, he died when Arthur was still young, in 1876. Thomas did not leave a fortune, but Arthur was sent to boarding school in Northampton. His mother didn’t remarry. She moved to Kettering, and Arthur moved in with her after he finished school. They lived on Silver Street, and Arthur worked as a veterinary surgeon, along with his older brother, Samuel James Marriott.

Eliza Jane Collier was born in Northampton in late 1864. Her father, Simon, was a shoe manufacturer in the town and they were affluent. It is unclear how she came to meet Arthur Marriott, but they married in Duston parish church on 8th September 1887. Arthur was twenty-one, and Eliza was almost twenty-three.

Their daughter was born almost exactly nine months after the marriage, and a son was born in January 1891. However, the marriage had already ended when little Harry was born, and Eliza had returned to her father’s house in Northampton. Arthur had gone to live with his mother in Milton. He later moved back to Kettering, living at Montagu House, at the junction of Montagu Street and Newland Street.

Eliza did not file for divorce until January 1893, a month after catching her husband in bed with another woman, Emma Walker. As I have mentioned before, divorce law was extraordinarily sexist and divorce was expensive. Men had to prove adultery against their wives to gain a divorce, and women had to prove cruelty and adultery, hence Eliza having to wait until she had proof of adultery – Eliza’s father had also been present when Arthur and Emma were found in bed together, to corroborate her story. Eliza had waited two years for this evidence, suggesting that Arthur had taken care to conceal his relationships, perhaps to avoid the stigma of divorce.

Eliza’s divorce petition makes for horrific reading. The petition opened with a description of their marriage and children, and two different adulterous relationships that he had had with Emma, and Annie Smith.

Then came the cruelty. Men were allowed to chastise their wives within reason, and reasonable chastisement was an extraodinarily flexible concept. However, no court could have found Arthur’s treatment reasonable, considering the family’s class. He had used foul language many times, used obscene language, had shoved her, threatened her, dragged her down the stairs. In November 1890, when she was heavily pregnant, he had driven Eliza ‘furiously’ through Kettering in a carriage and then pushed her out of it. He then threatened to whip her. He was drunk at the time, and a neighbour witnessed the act. Earlier that year, Arthur had beaten the horse pulling their carriage when drunk, and a passer-by had taken the horse and carriage away from him. On this occasion, Arthur was fined for allowing his gig to be used as a taxi!

It goes on. Arthur had withheld housekeeping money from Eliza – a terrible thing to do in a household where the mistress paid for everything, including servants’ wages, without having income of her own. Around the same time as the incident with the carriage, Arthur infected Eliza with venereal disease after having adultery with ‘some woman unknown’. Arthur took pleasure in teaching their daughter Daisy, then approximately three years old, to swear, and applauded her when she did so.

Quite aside from his violent and provocative behaviour, Arthur was also sexually abusing Eliza. He forced her to look at pornographic pictures and models, and told her that he would ‘force the modesty’ out of her. Marital rape was not acknowledged in English law until 1991, but it’s likely that he raped her. He certainly raped their servants – Eliza delicately described his attacks on three of their servants between May 1889 and September 1890: “he forced her to commit adultery with him”. After the third rape, Eliza decided she could not risk hiring servants to help her, and did the housework herself. She was in the last stages of pregnancy at the time, and described her health as ‘a ruin’ – her father testified in court to Eliza’s severe loss of weight in recent months.

Not content with raping their servants and showing porn to his wife, he then attempted to pimp Eliza out. In November 1890, when she was approximately seven months pregnant. Eliza woke up to a man in her bedroom. Nothing further is said about what transpired on that day, but later in the month, Arthur attempted to throw her out of the house. Eliza left on 28th November 1890, and went to live with her parents. She never returned to her husband, although their son’s birth was announced in the local press two months later.

Arthur appeared to be furious with Eliza’s father, Simon Collier. Around the same time as the man-in-the-bedroom incident, he grabbed Eliza around the throat, saying he’d like to throttle her father. Had Simon stopped lending Arthur money? In March 1891, Eliza took Arthur to court under the Married Women’s Property Act. Initially, the magistrate encouraged them to reconcile, but a month later, they appear to have made an arrangement. Arthur was certainly in financial difficulty by the summer of 1893, when he filed for bankruptcy, but this may have been an effort to avoid alimony.

Arthur did not contest the divorce, and the nisi was issued in May 1893 – a very rapid divorce by the standards of the time. The judge also gave custody of their two children to Eliza, an unusual move. The absolute was issued in November, three years after Eliza had run away from her husband. The judge ordered Arthur to pay Eliza £30 a year in alimony (about £14000 in today’s money), and the cost of the divorce.

Eliza remained with her family for the rest of her life. She did not remarry, and spent some time in Torquay after Arthur’s death, most likely for her health. She died in Northampton in March 1928, aged sixty-three.

Arthur left Kettering after his divorce, most likely to escape local infamy – although the newspapers shared no details about his sexual perversions, divorce was a stigma for the son of a Baptist minister. It is possible that his brother and business partner was also behind the move. In October 1894, he moved to Holbeach and joined a small veterinary practice on Barrington Gate, working for Albert Medd.

On 10th April 1896, Arthur took prussic acid in the surgery, taken from a drawer. He died alone, in the middle of the day, and was discovered by Mrs Medd when she went to offer him tea. He was holding a book of scripture, gifted to him by his mother, and had left notes for his mother, friends and brother – the note did not mention Eliza or the children.

Samuel Marriott travelled to Holbeach for the inquest, and gave misleading evidence. He claimed that Arthur had petitioned for divorce, making it seem that his children had been taken from him by an adulterous wife. He mentioned that Arthur had never paid the divorce costs. This evidence led the newspapers, and presumably the jury and coroner, to see his suicide in a sympathetic light.

Mrs Medd testified that Arthur seemed depressed at times, complained of headaches and was often drunk. He had spoken to her of suicide, specifically with prussic acid, but she did not take his talk seriously. The postmortem confirmed he died from prussic acid poisoning – hydrogen cyanide – and the jury returned a verdict of suicide while suffering temporary insanity. He was only twenty-nine.

Perhaps Arthur was a little insane – his behaviour in the final months of his marriage were not rational, but he could certainly manage his behaviour when he needed to. Perhaps time and distance had made him realise what he had missed – it is likely that Simon Collier, after going to considerable trouble to acquire his daughter a divorce, would have guarded his daughter and grandchildren at Northampton. It’s also possible that Arthur’s family had shunned him after the divorce. The book he was holding when he died was from his mother. It had been a New Year’s gift in January 1894, and was an almanac of scripture and the Psalms. Thomas Marriott was a Baptist minister: the family’s reaction to the evidence given in the divorce can only be imagined. Perhaps Arthur was simply ashamed.

Arthur’s burial place is unknown. It seems likeliest that he was buried in Milton Malsor, at his father’s former Baptist church.

Arthur’s children, Daisy and Harry, appear to have been fairly happy. Daisy married a hosiery manufacturer in Northampton, and lived to be 78. Harry emigrated to the US in 1910, eventually dying in Canada.

Thank you Linden, for letting me write this one up, and for the photo! Also, my friend Kathrina Perry is currently working on her PhD on Northampton shoemaking, and gave me some additional information on the Colliers. Thanks Kat!

SOURCES: Northampton Mercury: 24th April 1891, p7; 19th May 1893, p.5; 18th August 1893, p.6.

Lincolnshire Free Press: 14th April 1896, p.8

Marriott vs Marriott, 1893, England and Wales Civil Divorce Records 1858-1918(via Ancestry.co.uk)

Plus census, wills and parish records where appropriate.

One thought on “The Divorcé”

Comments are closed.