In honour of Diwali and Bonfire Night, my favourite time of year, here’s a story about what happens when fireworks go wrong.

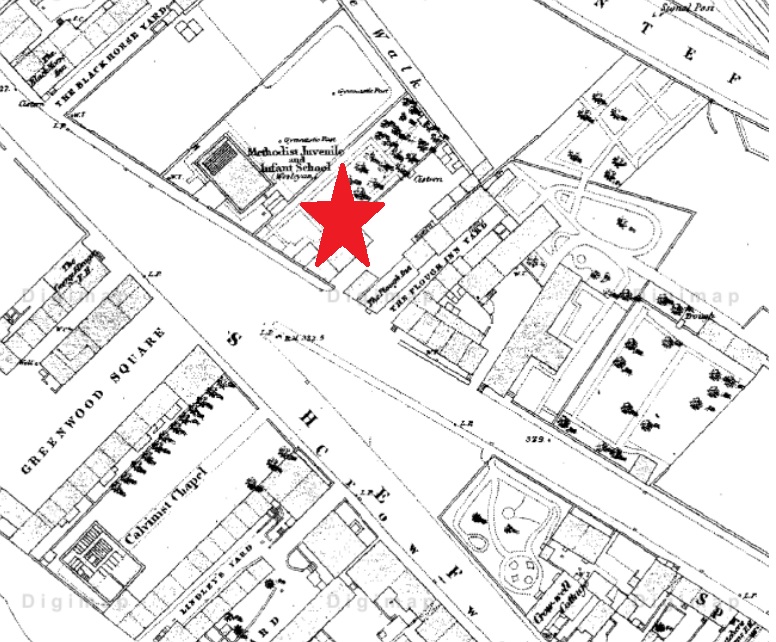

Barnsley, 1868. George Norris, aged thirty-five, was a man who provided luxuries: he was a jeweller, hairdresser, perfumer and he also had a small firework factory on the Doncaster Road, between the Wesleyan School and the Calvinist graveyard. The factory opened in 1865.

The factory was not purpose built, and consisted of a few sheds. George lived nearby in Sheffield Street, with his friend and co-worker Alfred Banks. He employed people from the local area, a network of courts and lanes around Taylor Row and Union Street. In October 1868, he had a staff of fifteen, and one assumes they were preparing for Guy Fawke’s Night. Most of the staff were working eighteen hour days to fulfil orders.

Work began as usual on 7th October, around 7am. George Norris was on site that morning, as was his foreman, William Elliott Bywater. The main working shed was long and narrow. It had one door, and at the other end, a stove. The stove was surrounded by iron bars, with one used to dry out powder that had got wet. The powder was usually dried in its separate components.

Maria Cooper was thirty-five. She’d worked in fireworks factories for years, and finished her shift the night before at 11pm. That morning, she was trying to fill Catherine wheels with composite – saltpetre, charcoal and sulphur, otherwise known as gunpowder – but the composite was wet. So, she placed a paper box of composite on the stove, with an offhand comment that she didn’t care if it blew up: she was in a hurry.

It seems Maria was in the habit of putting composite in tins on the stove to dry. Perhaps this was safer – I’m not about to experiment to find out. George Norris and his foreman, William Bywater, saw the paper box on the stove and simultaneously ran towards it to get it off.

They were too late.

The explosion threw William Bywater out of a window. The fire spread across the site, which was full of combustible material. Fireworks screamed into the air, exploding merrily over the carnage. Locals ran to the site, trying desperately to rescue the workers, and no water hose was found for over an hour. Meanwhile, the workers burned and died, tended to by their families and neighbours in nearby stables.

You see, there were no less than nine children among the thirteen workers. Two of them – Joseph John Siddons, aged ten, and Tommy Carrol, aged thirteen, survived. Six of the others died at the scene. Nine year old George Yates had only started work two days before. His father found him dying, screaming for water. Poor John Watson, aged eleven, had been at work for two weeks. He was trapped by flames in the corner of the factory shed. A stick was pushed through the flames to pull him out, but the skin on John’s hands came away on the stick, and the fire consumed him. Sarah Downing’s father had died a few years before, and she told her mother that she would “soon be with father”.

One child, Harriet Hinchliffe, an orphan who had been working in the factory since she was eleven, died in the workhouse the next day.

Maria Cooper was killed outright. Three other men died two days later. Richard Evans, aged nineteen, had lost his sister in the initial explosion. Both the Evans’ siblings lived with George Norris. George Norris also died, having never regained consciousness. William Bywater managed to give a statement to the police before he died. His statement ended: “I don’t think I shall get better. I have no feeling in my hands. I cannot write.”

There were four separate inquests after the fires were put out. The first was for the seven people who died at the scene, held at the Union Inn at the end of Union Street. This was held on the afternoon of the accident. Another was held on the 9th for Harriet Hinchcliffe, who died in the workhouse. The coroner returned to the Union Inn to cover the deaths of Richard, George Norris and William Bywater. A final inquest was held on the 13th October at the courthouse in Barnsley, after the firework factory had been inspected.

The inspection was damning. Ideally, the firework factory should have been a collection of small sheds, with no more than two people working in each one. At Norris’ factory, the entire workforce were in one shed. There was gunpowder everywhere, all over the floors. None of the sheds were suitable for storing or managing combustible material. The ventilation and exits in the work shed were inadequate.

However, the inquest jury decided to bring a verdict of nine counts of manslaughter against Maria Cooper, whose foolish, overtired, probably stroppy action had caused the death of so many. Maria’s own death was ruled death by misadventure. The jury added a rider: “[…]children of such tender years ought not to be employed in such dangerous occupations and […] there appear to have been no proper regulations in conducting the works and that the sheds were unfit for carrying on such business”. At the time, it was illegal to employ children aged under nine, so George Norris was legally employing these kids, although it’s likely that they were working longer hours than allowed in law.

Most of the dead were buried on the 9th and 11th of October, and their funerals were funded by George Norris’ estate. However, his estate refused to pay the medical costs of the survivors or to support the victims’ families, a very unpopular move in the town. Some fireworks manufacturers in London sent some money over for the victims, which was gratefully recieved.

I found this story years ago, while looking through the coroner’s notebooks for West Yorkshire. It stuck in the mind because the inquest blamed the only woman in the factory for the deaths, rather than the myriad problems with working conditions that led to an accident becoming a massacre. I hadn’t realised how young the children were.

Remember them.

Mary Ann Evans (1852-1868)

Jane Hawker (1854-1868)

Henry Howarth (1856-1868)

Sarah Ann Downing (1856-1868)

Harriet Ann Hinchliffe (1855-1868)

John Edward Watson (1857-1868)

George Yates (1859-1868)

SOURCES: West Yorkshire County Coroner’s Notebooks, Ancestry and the Barnsley Independent.

Get in touch with your own family research problems and questions using the contact page above.